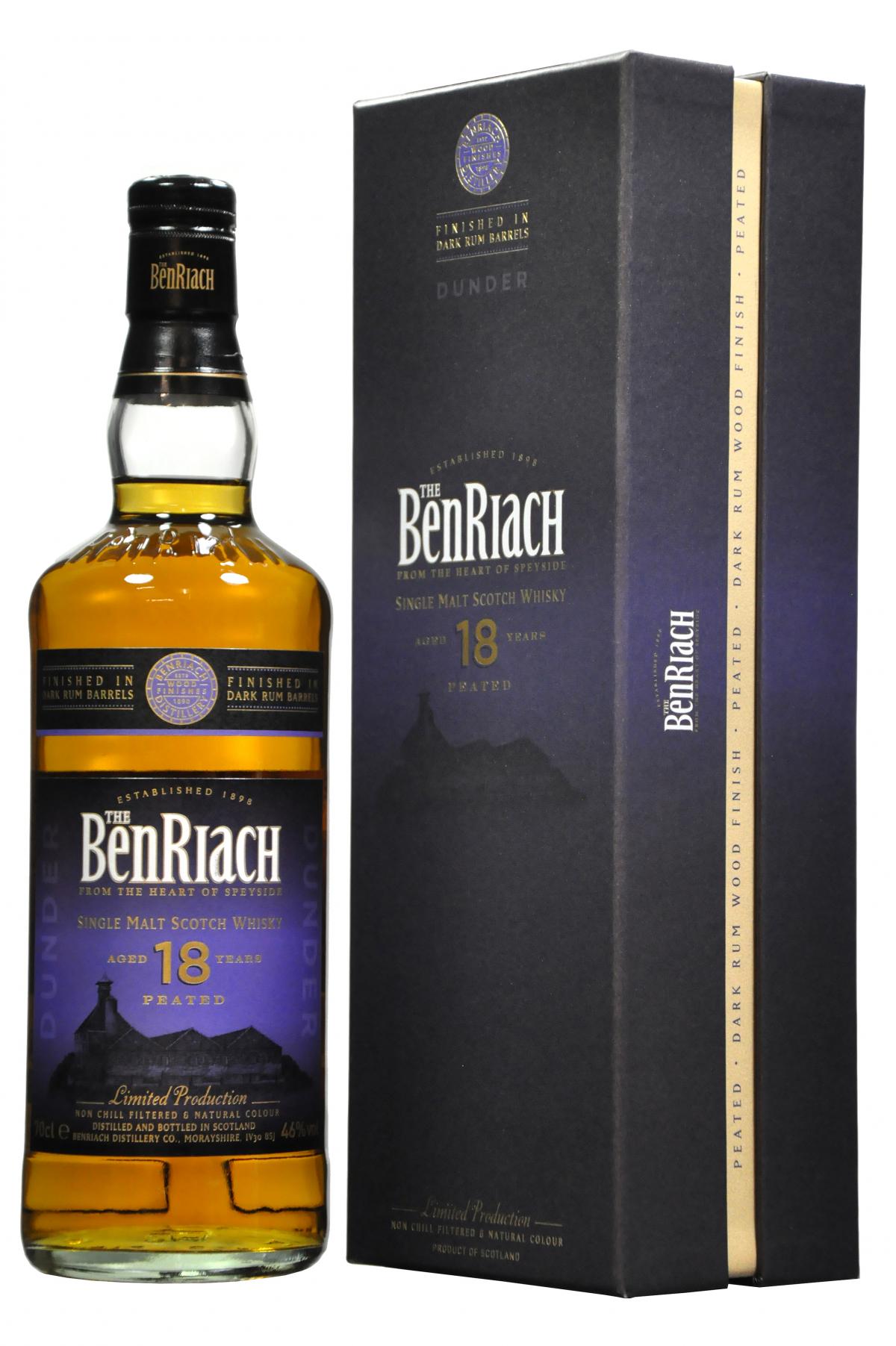

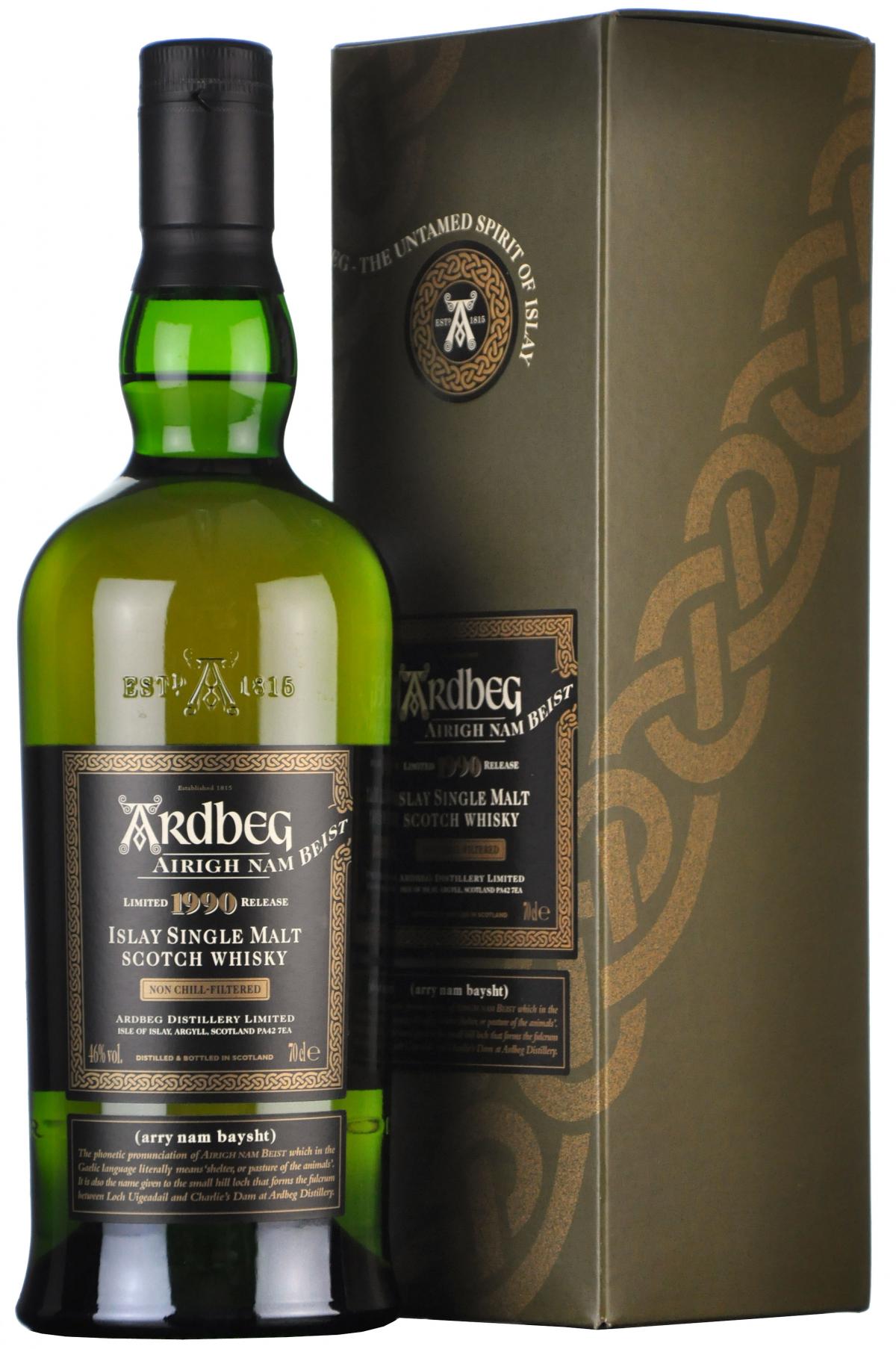

Great whiskey Definitely a recommendation for any peated whiskey fan as you can probably tell by its name haha

The whisky arrived promptly and didn't disappoint. The whisky, with a few drops of water, was super smooth despite the 51% alcohol. As always, the sherry cask enhanced the flavour - another great un-peated whisky from Bunnahabhain.

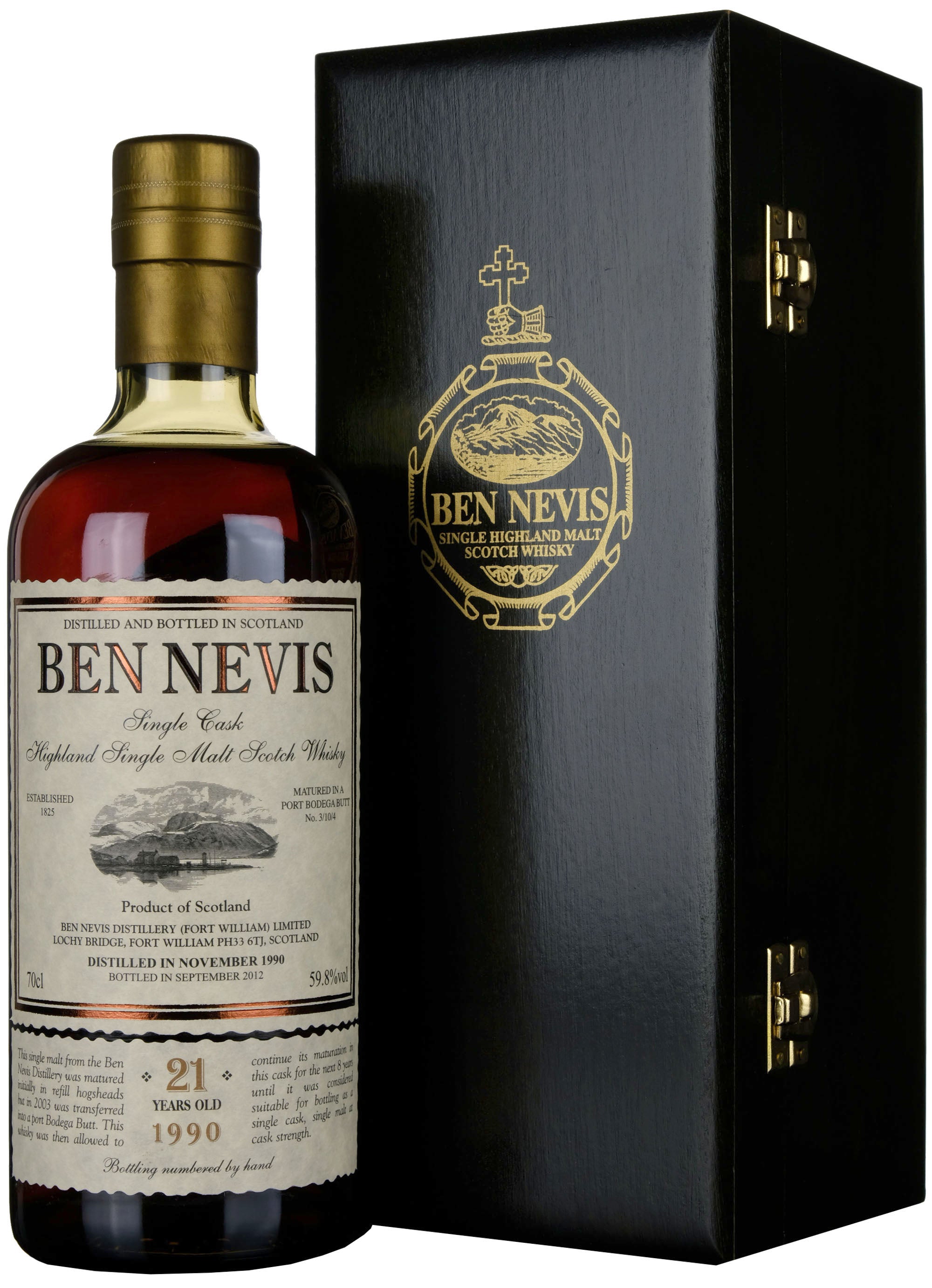

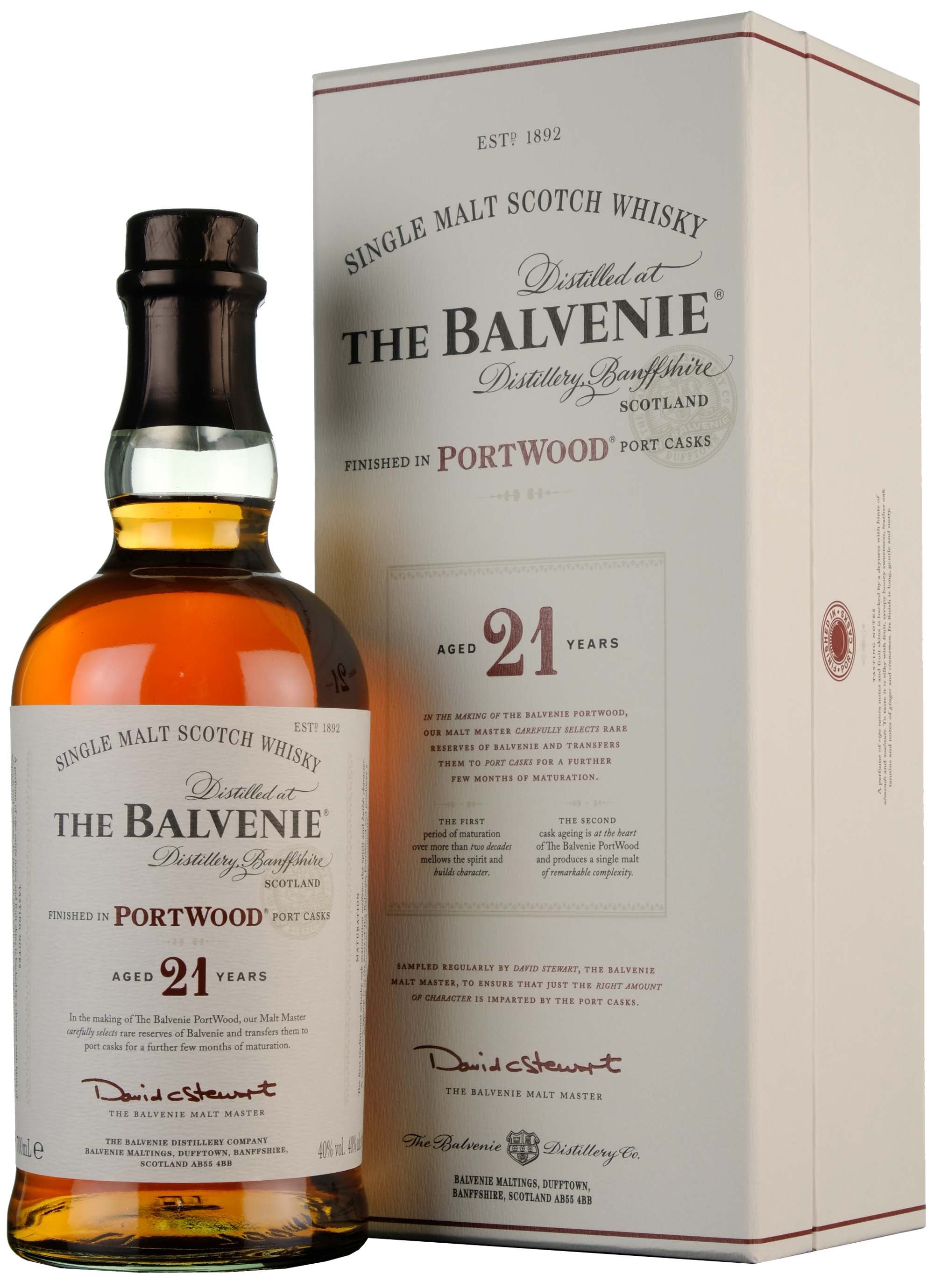

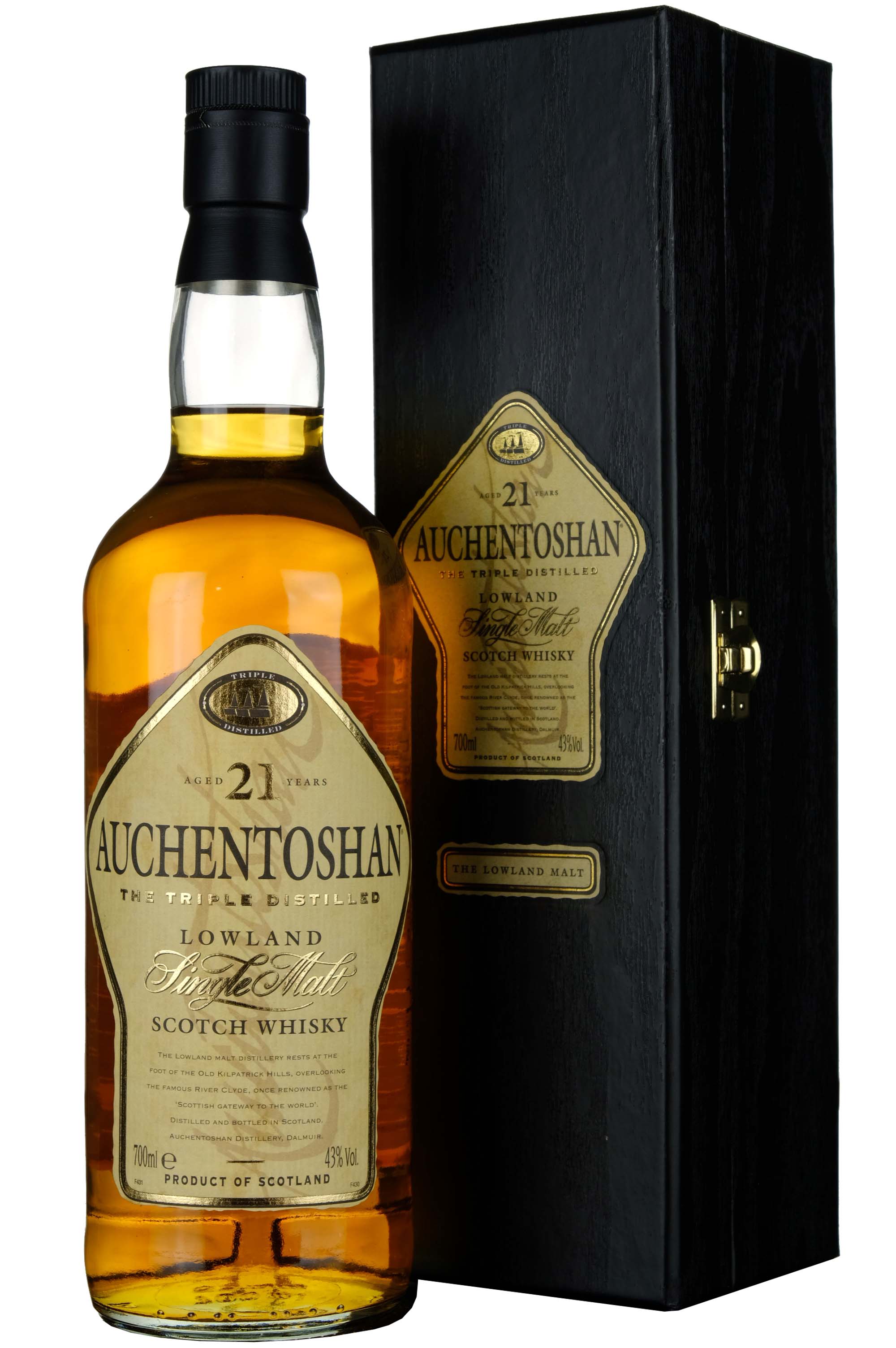

I haven't had the opportunity yet to try my whisky ( which I ordered at the same time) I'm planning to try it, in the free gift, in May to celebrate our 21st wedding anniversary. I've always been satisfied with Whisky Online Shop, great company to deal with. Thank you.

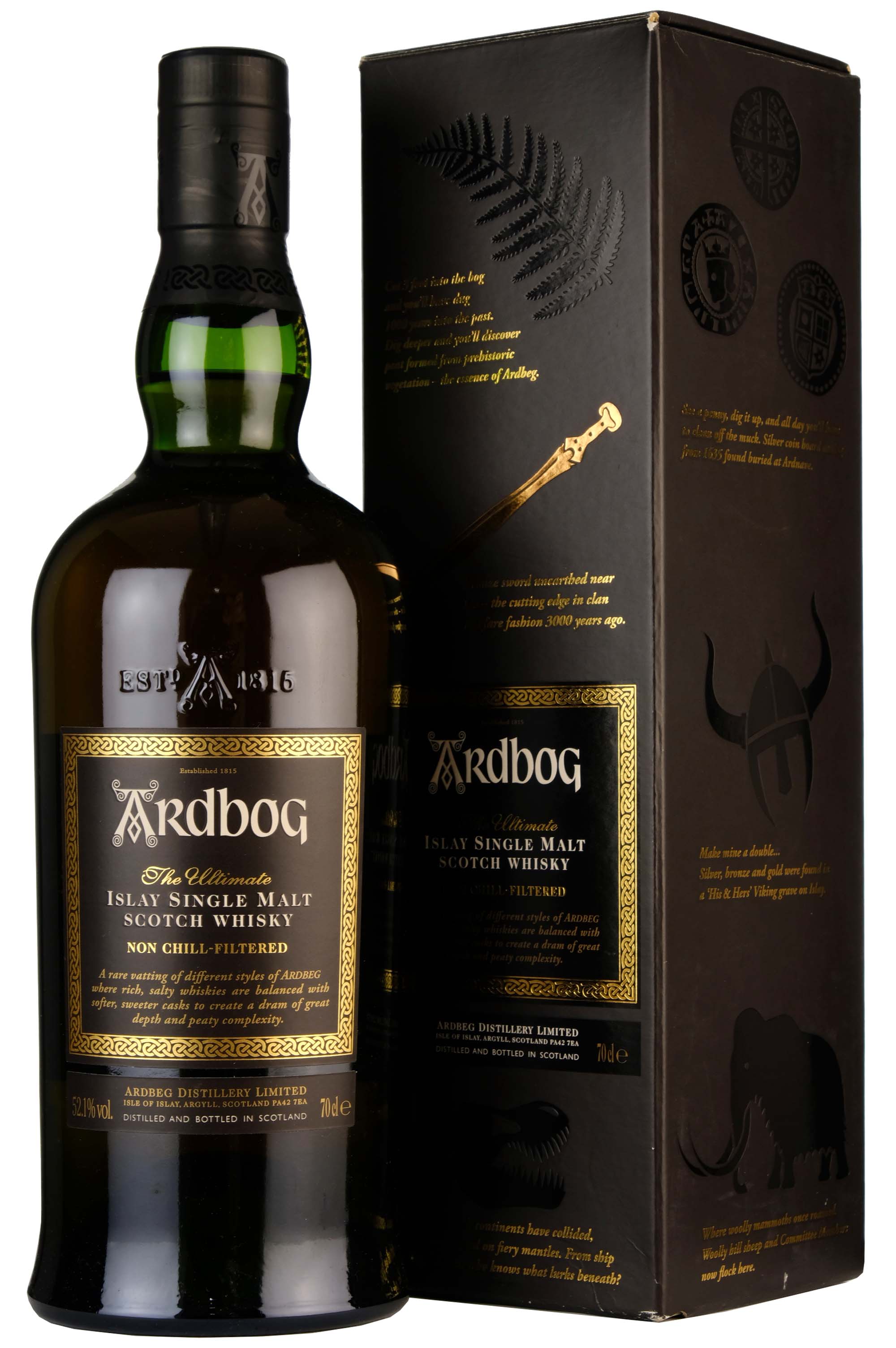

Just a lovely dram